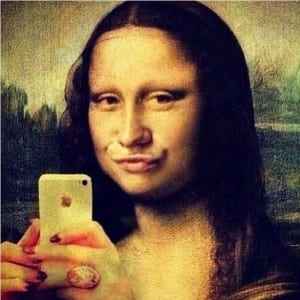

When questioning the role of originality and the nature of artistic reproduction, we have found John Berger to be a great influence. In his 1972 documentary series, “Ways of Seeing”, Berger examines the way that tv and the camera change the way art could be accessed by the public. The camera is free “from the boundaries of time and space”, because it can transmit images to a screen, or keep a saved copy within its hardware to show at a later date. The fact that artworks can be saved, broadcast or transmitted across the world opens up a wide range of possibilities for the way the public interacts with art. By now, most people will have seen the parody images of what the Mona Lisa might look like if she had an Instagram account, an image that would not have existed without the invention of photo-shop software. This is just one example of the way that the originality of an art work can be compromised by almost anyone, and uploaded to the internet for the world to see with little effort.

Although that may be an extreme example, a quick search of the market website amazon.com reveals a multitude of replicated Mona Lisa posters for sale for as little as £3.75. On a higher price scale, an oil paint copy can also be purchased for £349. This stands out from other copies because it is oil on canvas like the original, and approximately the same size. It is reasonable to assume that this was not copied in the gallery itself, meaning that the artist most likely painted the piece from an image found on the internet or in a book. Given these previous examples, it should be no surprise that John Lichfield described the Mona Lisa as “the best known, the most visited, the most written about, the most sung about, the most parodied work of art in the world”. The wide renown of this piece is due in no small part to the ease of which it can be accessed through the internet and media.

Recent Comments